The Indo-Japanese Pivot to Africa

In pursuit of a robust strategic partnership, India and Japan are broadcasting their desire to work together far beyond South Asia, with an emphasis on Africa. Their vision for an Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC) lacks detail, but still offers an opportunity to raise both countries’ profile in a strategic continent. To compete with China’s presence there, however, India and Japan will have to show that they are committed to the continent and that they can deliver not just on quality but also on speed.

The four India-Japan joint statements released since Prime Minister Modi took office show a clear growth in the ambition for activities beyond India. The 2014 statement primarily emphasized Japanese investment in India; when it ventured abroad, it did so in the context of building connectivity between India’s Northeast and Southeast Asia. Africa does not feature until the 2016 statement, which promises “India-Japan dialogue” to explore partnership in “the areas of training and capacity building, health, infrastructure and connectivity.” The 2017 statement takes this a step further, describing a shared commitment “to explore the development of industrial corridors and industrial network [sic] for the growth of Asia and Africa.”

The AAGC concept first appeared between the 2016 and 2017 statements, in a vision document authored by three government-sponsored think tanks. Despite the name, it’s far from clear that the AAGC will take the shape of an actual semi-linear route along the lines of the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor. Instead, much like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the AAGC is envisioned as an investment and outreach package. It has four main pillars: “development and cooperation projects, quality infrastructure and institutional connectivity, capacity and skill enhancement, and people-to-people partnerships.”

The original Indo-Japanese goal of better connectivity between India and Southeast Asia is far from achieved. South Asian connectivity as a whole remains remarkably poor; Japan’s interest in participating in an India-led initiative to develop Iran’s Chabahar Port illustrates the opportunities for infrastructure cooperation in India’s “near abroad.” So why Africa? What has spurred the two nations to look so far afield for opportunities?

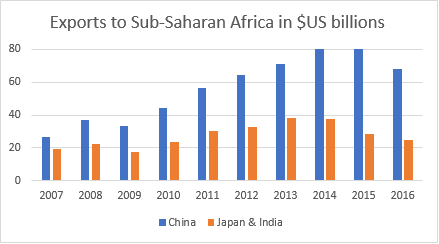

There are two important reasons India and Japan settled on Africa as a field for cooperation. The first is the most obvious: economic potential. Despite India’s close historical and diasporic ties to the African continent, as well as its geographic proximity, Indian and Japanese exports to Africa lag far behind those of China.

China’s economy, of course, is far larger than that of India and Japan combined, and thus a dollar-for-dollar comparison is not entirely fair. The situation is rather different when we look at exports to Africa as a percent of total exports: it’s clear that Africa is an important market for India, especially for refined petroleum. By contrast, less than one percent of Japan’s total exports went to Africa in 2016.

From India’s perspective, furthermore, increasing trade with Africa fits well with its developing trade strategy of focusing on markets where its high-value goods are competitive. India’s 2016 Capital Goods Policy, for instance, suggests reorienting trade promotion efforts towards African countries and other developing nations, as opposed to focusing on trade agreements with developed countries. And India is well-positioned to take advantage of African growth: eastern Africa, one of the most economically vibrant areas of the continent, has a large Indian diaspora and is relatively close to ports on India’s west coast. The AAGC builds on existing Indian efforts to build ties with Africa, including the 2015 India-Africa Forum Summit.

The map of African growth, however, shows some of the drawbacks of this strategy. While the continent’s economic picture is highly diverse, with a few strong performers, 13 African nations are growing at less than 2 percent a year, according to the World Bank . It will be difficult, although certainly not impossible, for Japan and India to grow their exports in the context of slow or zero growth.

But the AAGC does not have a purely economic rationale. The second reason for a joint Indo-Japanese project focusing on Africa is explicitly political and strategic: it is an opportunity for the two countries to show what they can do outside of the South Asian region. The AAGC offers a riposte to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (which focuses mainly on Central and Southeast Asia) and also to China’s ongoing investment and trading activity in Africa.

It’s no secret that over the past 15 years China has made major investments in Africa; its greenfield FDI in the continent surpassed that of the United States in 2015 and 2016 and is on track to do so in 2017 as well. China has such strong ties with African nations such as Zimbabwe and Ethiopia that the general who led the recent coup in Zimbabwe sought Chinese approval before moving against long-term leader Robert Mugabe.

But despite the hype surrounding Chinese power in Africa, much of it driven by China’s penchant for announcing blockbuster investment totals, there’s room for competition. For one thing, the actual value of Chinese investment is less than fears of Chinese influence over the subcontinent would suggest. The Johns Hopkins China-Africa Research Initiative (CARI) estimates that China lent Africa roughly $94 billion between 2000 and 2015, with $11.8 billion of that total coming in 2015. To put this in context, in 2015 the OECD nations lent $36.4 billion to the continent. Furthermore, Chinese funds are far from evenly distributed. Angola and Ethiopia together have received $32.3 billion, more than a third of the total. In 2015, 36 African nations did not receive any loans from China. If Japan and India target their investment wisely, they can quickly become major players.

CARI data on FDI also shows that Chinese dominance is far from assured. In 2015, the stock of Chinese FDI in Africa stood at $34.7 billion, with net inflows of $3 billion. American FDI in the continent, in contrast, stood at $64 billion. As with loans, many nations received minimal Chinese FDI—28 states received investment of less than $25 million.

China’s relatively modest, if high-profile, investments have won it widespread popularity in Africa. A survey of citizens of 36 African countries found that 24 percent of those surveyed preferred following China’s model of economic development, compared to 30 percent who picked that of the United States and 2 percent who favored the Indian model. More than 60 percent of Africans have a positive view of Chinese activities.

India and Japan are unlikely to match Chinese investments in the near term. The AAGC is unlikely to compete with money alone, however. As mentioned in the vision document, the AAGC hopes to spur “people centric sustainable growth” by engaging a wide range of stakeholders and providing infrastructure that’s built to last. It’s undoubtedly true that many Chinese-funded projects don’t adhere to the high environmental and social standards crafted by multilateral lending agencies. China also tends to build and finance projects that multilateral lenders find too risky. India and Japan are calculating that the African people are hungry for a more equitable and transparent alternative, even if it means more expensive projects or longer timelines. But they may also need to match China’s willingness to take on projects that would not receive funding from more traditional sources.

Indo-Japanese cooperation to develop Africa offers clear-cut strategic benefits. The Chinese example suggests that gaining influence and building trade in Africa is as much about consistency, visibility, and engagement as it is about the actual dollar value of investments. And given the continent’s needs, there is certainly more than enough room for all three countries to be big players in Africa. But India and Japan will have to work hard to execute projects with speed and efficiency if they are going to reduce China’s lead in the region. Quality, quickly, is the key.

Sarah Watson is a former Associate Fellow with the CSIS Wadhwani Chair for U.S.-India Policy Studies.